My trip to India

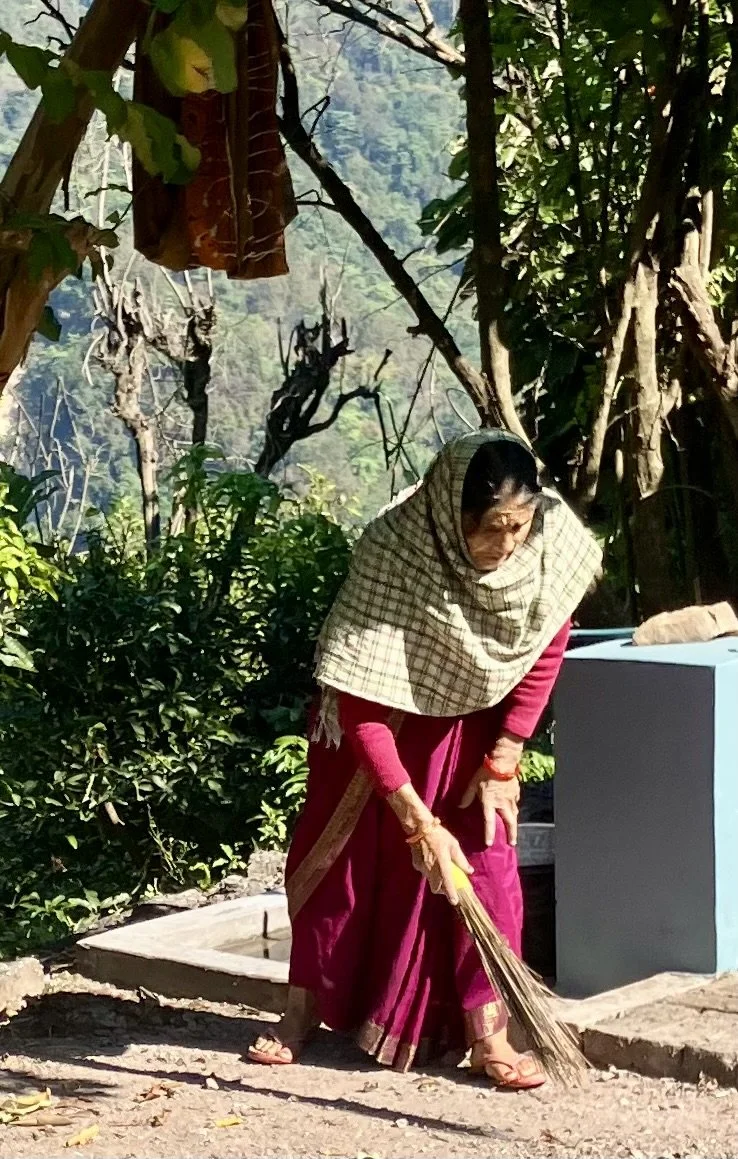

A moment in daily life, a grandmother and her granddaughter. … One of my favorite memories of a family living in the mountains of Rishikesh.

By Cara Chang Mutert

I left for India with so much anticipation. To return almost 50 years later to a place I remember so fondly in my heart. A world that has shaped so many of my values and perceptions.

Upon returning, I felt so much gratitude (and a good amount of relief) to come home to the US and surprised at my feelings about it all. I felt shell-shocked and almost disappointed in myself about all the comforts I’ve grown so accustomed to. At the same time, I couldn’t be more grateful for all my life has afforded me. I thought I could rough it, because I have before, but I didn’t expect the emotional toll of what I experienced.

After a few weeks of being home, processing and re-integration, I have more clarity about it all. The trip was undeniably beautiful and memorable, moving and meaningful. It was also enlightening and difficult, stunning, and challenging.

The dirt and grit. The garbage. The crowds of people. The horns of motorbikes and tuk tuks blasted everywhere. The noise and chaos was somehow endearing to me. It was so reminiscent of what I experienced as a child growing up in that region during the early 70s. I hungrily looked outward just to soak in all the sounds, smells, and culture that I remembered so well.

Since I lived there as a child from ages 7-13, I thought I was prepared for it all. The memories were clear. I knew there would be beggars. I knew there would be crippled people rolling around in makeshift contraptions to wheel their broken bodies around to ask for money. I remembered the hungry children and starving dogs. Or at least I thought I did.

But things felt different this time. I expected to see poverty, but the depth of much of the suffering was hard to witness. Things hurt more. Everything made me tired.

I discovered my more porous, absorbent, sensitized adult self was no longer able to filter the suffering. I avoided eye contact whenever possible, knowing this was the best way to avoid attention and become a target for more and more hungry, begging children. I found it difficult to remain unaffected by it all. I realized I had developed a deeper compassion for the suffering after 50 more years of life and living.

As an adult, I now understand it all as a result of conditioning, poverty, desperation, and overpopulation. More specifically, it stems from a lack of education and training, and moreover the years of oppression in a caste system which has hummed silently yet effectively under the colorful tapestry of this beautiful country for thousands of years. Sadness arose, along with feelings of despair and hopelessness on their behalf.

Meanwhile, I found myself challenged by the lack of creature comforts I’ve grown so accustomed to. Things like hot water, safe drinking water, a warm room, and sanitation standards. I felt spoiled and a little frustrated with my very American self. Contrasting my relatively lush accommodations with the hovels, tents, and lean-to’s peppering every corner, I was conflicted by my own feelings of selfishness to want to be comfortable with the unfathomable conditions of so many others sleeping just around the corner from me.

And then there were the animals. Hungry dogs were everywhere, many of them with open wounds, sores and protruding ribs. They slept wherever they collapsed. But just like all the opposites I encountered there, the animals offered me both an ache and a comfort. The sweet eyes of each cow, the curious opportunistic energy of the humanlike, obviously intelligent monkeys, and the dogs… each one doing their best to survive, just like the people. And still, just hungry for love, comfort, and attention.

The paradox was the stunning beauty of the country. The beauty of the people. Their devotion. Their faith. The exhilarating, colorful, and moving rituals. The magnificence and artistry of the structures built long ago to forever commemorate the death of royal loved ones. The soaring green mountains and undeveloped forests that carpeted the North. The colorful bazaars and vibrant saris. Every local woman, poor or otherwise, was draped in bright colors highlighting their beautiful dark and weathered skin. As I watched a group of gray-haired women ceremoniously wash themselves in the Ganges River, I saw the pure joy in their faces. More than ever, these bright moments of light shined through.

One of the more touching moments, among many, was a hike we took one morning up the mountain to a small, unassuming local temple honoring Durga, the Hindu goddess symbolizing the divine strength, magic, and power of the feminine. On this hike, we saw families with basically nothing, not only surviving but seemingly thriving in the mountains, living off what they could grow themselves, a cow or two, and even a pet dog. There was the smiling young woman cutting down the high grass with a sharp machete; another grinding food by hand, and a bit older one washing clothes by hand scrubbing them on the cement landing; a man breaking stones by hand with a small mallet, about one foot up into building their next living structure, perhaps for themselves or their animals; and another older woman sweeping the entrance to her abode with a broom made from branches.

They were living as they always have and seemed content to do so. It was such a poignant moment to witness a small group of locals who’ve clearly lived lives riddled with difficulty and challenges, but also with a sense of acceptance and even happiness and contentment behind their eyes. These were the faces I’ll never forget.

It was here that I came to understand why this is the land in which yoga was born. It offered me a felt experience through the eyes of its people of what yoga, in all its centuries of wisdom, has tried to teach us. With extreme hardship comes faith in something larger than life itself, and with it, a sense of gratitude for the simplest of things: to see the light in the darkness, to see hope in despair, to find comfort in the difficulty, and to share love openly and freely when there is nothing else to give.

As I boarded the plane, eager to return to all that I missed about the US, I realized that was one of the truest lessons of this trip and of a lifetime: To find acceptance in what life presents to us, to stay grounded in the goodness and beauty that is, to learn to find contentment in all that surrounds us, and above else, to love one another, for that is all we know for sure.